Last month I was able to attend the International Forum for the Council of Christian Colleges and Universities in Dallas. Side note: there are people in Texas who wear cowboy hats and doughnut-sized belt buckles unironically. Side side note: one of them spent the entire hour before our flight spitting dip juice into an iced tea bottle.

Anyway, the plenary sessions alone were worth the trip. Bryan Stevenson held us riveted for an hour (“Doing justice means proximity to those suffering injustice. Our faith is rooted in the power of proximity; we cannot make a difference from a distance”) and Jemar Tisby BROUGHT IT (“Jesus saw, had compassion, and healed. How can we have compassion or bring healing if we say we don’t see color?”).

I knew these sessions would be powerful, but I was unprepared for how significant the afternoon session with Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett proved to be. You may recognize Putnam’s book Bowling Alone or know him as a professor of public policy at Harvard. Romney Garrett is also an author and a social entrepreneur. Together, the two have written The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. I wish every American had heard their presentation.

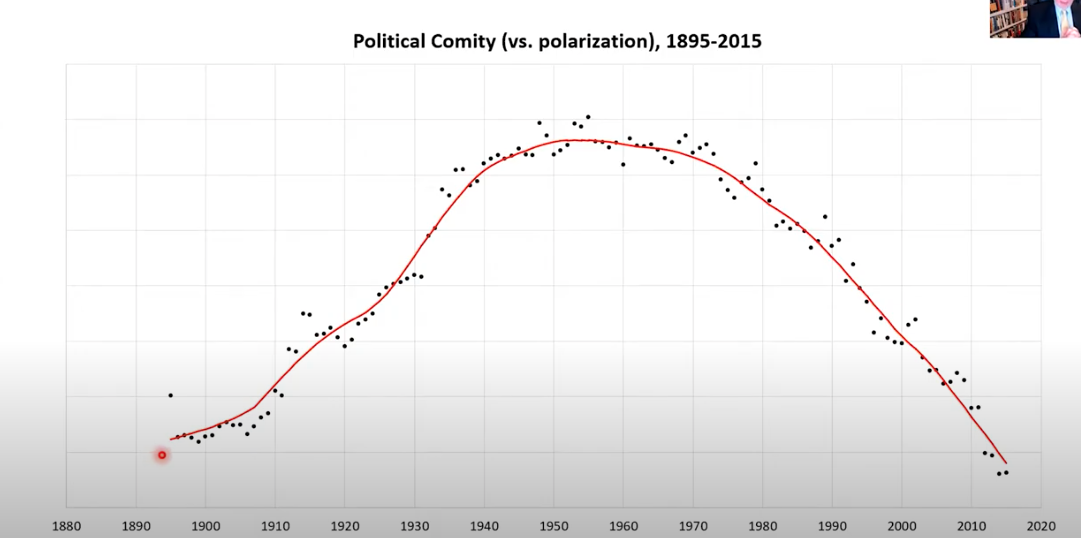

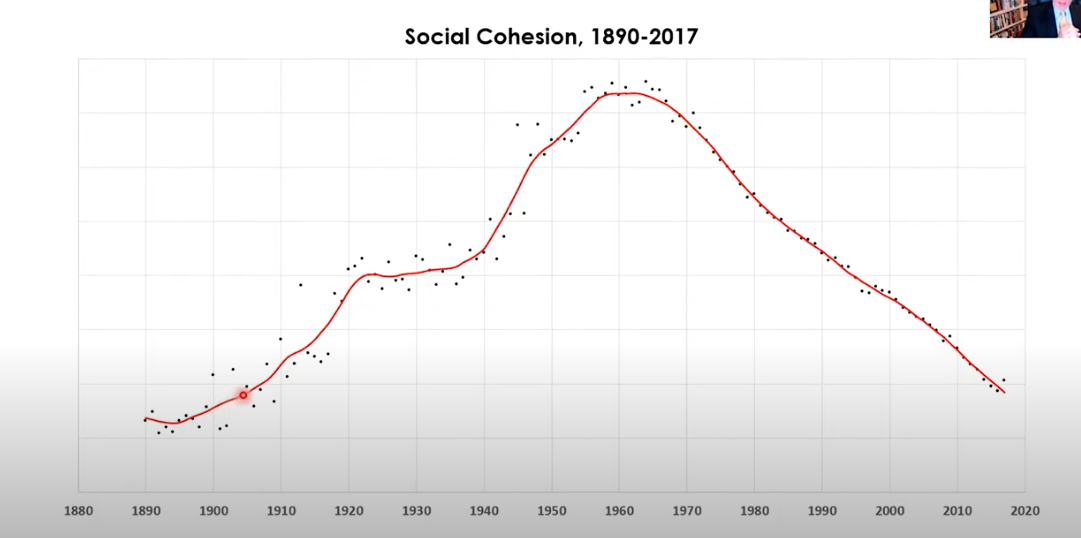

The TL;DR is that the two authors analyzed enough data to choke a camel and discovered “an unmistakable—even breathtaking—pattern” when comparing the United States now and the United States during the Gilded Age at the turn of the last century. In four key areas—political cooperation, economic equality, social cohesion, and cultural solidarity — “the trend line looks like an inverted U, starting its long upward climb at roughly the same moment, and then reversing to a downward descent within a remarkably similar time frame.”

The TL;DR is that the two authors analyzed enough data to choke a camel and discovered “an unmistakable—even breathtaking—pattern” when comparing the United States now and the United States during the Gilded Age at the turn of the last century. In four key areas—political cooperation, economic equality, social cohesion, and cultural solidarity — “the trend line looks like an inverted U, starting its long upward climb at roughly the same moment, and then reversing to a downward descent within a remarkably similar time frame.”

In other words, in the first years of the 20th century, we were more politically polarized, more economically and socially divided, and more narrowly focused on our own interests than at any other time in history—until now. From the beginning of the century until the 1950s, we steadily grew more able to compromise politically, more committed to community over self, more socially united, and more economically equal. Beginning in the 1960s, these trends started to reverse. (Photo credits this video.)

Today we are in crisis again, which isn’t surprising considering the last downswing happened after the Industrial Revolution and the Spanish Flu and we are now getting our bearings in the midst of the Information Revolution and Covid.

So, this is interesting because it’s highly unusual for the data to track so closely across four measures and across a century. But it’s important because we got out of this toxic mess once before – and if we learn from that, we can do it again.

Putnam and Romney Garrett identified the following insights from the last time our country worked itself out of crisis, a hundred years ago:

Putnam and Romney Garrett identified the following insights from the last time our country worked itself out of crisis, a hundred years ago:

- The upswing was led by young people.

- Efforts began at the grassroots level, not at the federal or state level.

- The most important turning point was a cultural and moral re-awakening. This began, ironically enough, by evangelical pastors and theologians who began questioning what we owed to each other as humans, and who recognized the full measure of faith is not just salvation from sins but serving and loving other people.

- Another key was “chastened elites” (mostly young) who realized how much they’d benefited from the economic inequality and who joined in the local change efforts.

- Charismatic leaders pushed things that were building momentum, but didn’t initiate them.

- Economic equality was the last of the four measures to improve.

What is my point? Let’s recap: Dip is disgusting, yay for professional conferences, read everything Stevenson and Tisby write, and, in the words of Whitney Houston, the children are our future. For real though: you and I can make a difference, but we should look for the young leaders working to bring shalom and justice in our communities. We should platform and resource them to keep it up. We should continue to call our own faith communities and their leaders to a reckoning about whether we are living up to our own values as Jesus-followers.

And we should not give up hope that “the wrong shall fail, the right prevail,” even if it takes a decade or three. Young leaders and Christians can lead the way as they have in the past—imagine what young Christian leaders can do! I’ll travel with cowboys all day long if it means being reminded that my small part in one small institution can lead to real change. Johnson students—let’s go.

Leave A Comment